By Christopher Rhoads

The arrival of the Internet brought a rare bit of good fortune to Niue, a tiny, impoverished island in the South Pacific.

Its national Internet suffix, dot-nu, has become a big hit in Sweden, as “nu” means “now” in Swedish. An entrepreneur in Medfield, Mass., named Bill Semich, who acquired the rights to operate and sell the dot-nu domain name in the late 1990s, has plowed some of the profits from Sweden into making Niue (pronounced New-Ay) the world’s first nation with free wireless Internet for all of its citizens, about 1,200 people.

But that success has thrown the island, which is about 1 1/2 times the area of Washington, D.C., into turmoil. Some officials charge they were cheated out of what they now see as an important and profitable national asset. “This is a huge issue of national development for us,” says Richard Hipa, the managing director of Telecom Niue. “This is something that we should have run, and we were robbed of that.”

The island’s government has locked horns with the 62-year-old Mr. Semich, whose company is called .NU Domain Ltd., demanding a bigger slice of profits and more control over the domain name. The fight prompted a nearly three-year independent investigation launched by the government and became the dominant issue in the island’s elections last year.

The island’s government has locked horns with the 62-year-old Mr. Semich, whose company is called .NU Domain Ltd., demanding a bigger slice of profits and more control over the domain name. The fight prompted a nearly three-year independent investigation launched by the government and became the dominant issue in the island’s elections last year.

“The fact that we are making this extremely large and voluntary commitment to Internet service on Niue is unprecedented,” says Mr. Semich from his spartan Medfield office. A small painting of a Niuean landscape adorns one wall. He argues that what he provides is worth more than cash. “To take that and turn it on its head and say, ‘You should pay more,’ misses the whole point.”

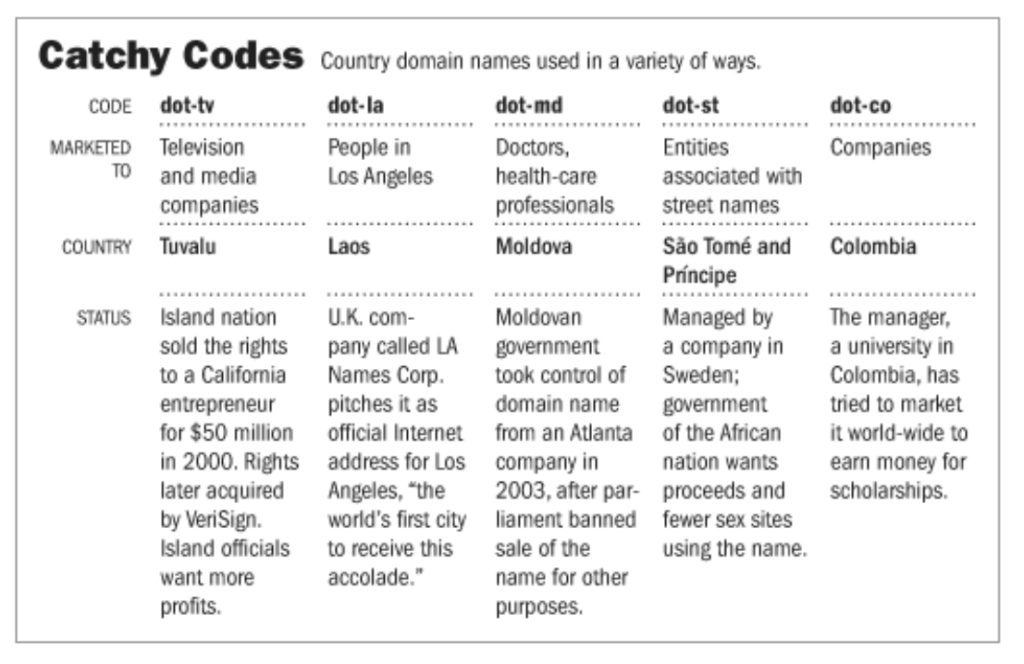

As Internet use explodes, governments around the world, particularly in developing nations, are discovering the power of their once-obscure country-code domain names. They have begun to see the names as a source of revenue, a way to increase their presence in cyberspace and as part of their national sovereignty — like the highway system or phone company — to be managed as they see fit.

More than a dozen governments or quasigovernment organizations have gained control of their country-code domain names in recent years. Usually the names have been wrested from individuals managing them since the 1990s — often before the governments were aware of the Internet.

Selling Bluegrass.ky

In 2004, France passed a law to legitimize its control over domain names of its overseas territories, such as Mayotte (dot-yt) and St. Pierre and Miquelon (dot-pm). A couple of years ago, the Cayman Islands obtained control of its domain name, dot-ky, from a U.S. entrepreneur marketing the name in Kentucky. He had sold bluegrass.ky and horsecapitaloftheworld.ky, among others. Kazakhstan and South Africa have also battled to win back control of their domain names.

The body that makes such decisions, an arm of the nonprofit Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, or Icann, in recent years has recognized each nation’s “sovereign control” of its domain name, according to a policy statement. Previously, the organization, based in Marina del Rey, Calif., would transfer control of a domain-name suffix only if it were “in the best interests of the Internet community” and if both parties agreed to the change, according to its statements.

After slowing in the wake of the Internet bust six years ago, domain-name registrations have soared. The global total jumped by nearly half to 94 million in the two years that ended last Dec. 31, according to Zooknic, an Internet research firm based in Louisville, Ky. Much of the growth is coming in developing nations. The number of domain names using China’s dot-cn and India’s dot-in each more than doubled last year, according to Zooknic, well ahead of the 40% increase of names using dot-com.

Country-code domain names were conceived in the early 1980s by Jon Postel, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California, as a way to help organize addressing of the Internet.

Country-code domain names were conceived in the early 1980s by Jon Postel, a computer scientist at the University of Southern California, as a way to help organize addressing of the Internet.

Each computer connected to the Internet is given an identifying series of numbers, called an Internet protocol address. To make an IP address more user-friendly, each one has a corresponding domain name. Just as dot-com was set up for commercial entities, country-code domain names were to identify users by country.

Reflecting the collegial and informal nature of the fledgling Internet community at the time, Mr. Postel assigned operation of the domain names to trusted friends or people he knew. They were mostly like-minded academics and computer engineers who performed the work on a volunteer basis.

The administrative contacts for each country code had to reside in the given country and understand they were “performing a public service on behalf of the Internet community,” Mr. Postel wrote in a 1994 memorandum codifying the domain-name structure. Typically, he decided who would manage country codes for distant nations on a first-come, first-served basis.

In the early and mid-1990s, this was happening below the radar of many governments, some of which viewed the Internet as a passing fad.

Still, Mr. Postel understood the political ramifications of country-code domain names. To avoid having to determine what constitutes a country and make up domain names for them, he used the two-letter codes from a list, called ISO 3166, compiled for mail and other purposes by the Geneva-based International Organization for Standardization. Any territorial entity on the list would get a domain name.

Many of those listed weren’t countries. Some were homes only to penguins. The Indian Ocean made the list, dot-io. Specks of land belonging to other countries were included, such as the United Kingdom’s Pitcairn Island, a South Pacific island whose population consists of 50 descendants of the mutineers of the HMS Bounty and their Tahitian wives. (Niue governs itself in “free association” with New Zealand.)

Mr. Postel, who died in 1998, viewed the domain names as merely an administrative convenience. But others, such as Mr. Semich, the head of the company at odds with Niue’s government, saw a business opportunity.

“It never occurred to Postel that the value of the revenue generated by domain names could be greater than the value of the Internet service itself,” Mr. Semich says.

As an editor for a computer trade magazine in the 1990s, Mr. Semich followed the Internet’s early development closely, taking note of the skyrocketing demand for new Internet domain names. He also plunged into the Internet policy debates at the time that included the creation in 1998 of Icann, which took over the duties handled by Mr. Postel.

That same year, Mr. Semich quit his magazine job and got into the business full time. He started a small software company offering clients the ability to have domain names in languages that don’t use the Roman alphabet. And he trolled about for available domain names that seemed marketable. He settled on dot-nu, thinking it would be a catchy domain name for U.S. companies looking for a cheaper alternative to dot-com. At the time, a new dot-com address cost $100 to register for two years. After lining up the necessary servers, contacts on the ground in Niue and approval from Icann — a process that took several months in all — Mr. Semich was up and running.

Icann required only information that he had the technical capabilities to manage a domain name. There was no fee. But Mr. Semich did spend about $100,000 on servers and other equipment to get the business started.

The expression of interest from an American entrepreneur was at first warmly welcomed by Niue, which hasn’t had many breaks over the years.

With its closest neighbor, Tonga, more than 350 miles away, Niue ranks among the most remote places on Earth. British explorer Captain James Cook got a bad taste of the island when he visited in 1774. After shouting natives chased him and his crew away, he dubbed the place “Savage Island.” Subsequent settlers were surprised to find vegetation on the chunk of coral rising from the sea, calling the place Niue, which in the local language means, “Look, there’s a coconut.” When Niue finally built an airport in 1971, thousands of Niueans used the opportunity to emigrate.

Along with selling local stamps and fishing rights, the biggest source of revenue for islanders is foreign aid. The government is by far the largest employer. In January 2004, a mammoth cyclone devastated much of Niue, prompting even more to emigrate.

When Mr. Semich arrived on the scene, he says Telecom Niue wasn’t interested in the domain name or in offering Internet service, because it feared the Internet would sap its revenue from faxes. Mr. Hipa of Telecom Niue says the government was just beginning to formulate an Internet policy but believed the domain name was just “like an international dialing code prefix.”

Mr. Semich hired two expatriates on the island: Richard St. Clair, a former Peace Corps volunteer from San Jose, Calif., and a New Zealander named Stafford Guest, who runs a hotel and bar. Their chief task has been to erect Internet service on the island.

Mr. Semich’s initial plan to market dot-nu to U.S. customers mostly flopped. Dot-com’s big lead over other domain-name suffixes made dot-com even more appealing for new users. But before long, Mr. Semich found that some Europeans, in particular Swedes, took a liking to dot-nu.

At the time, Sweden’s country-code domain name, dot-se, was reserved only for companies incorporated in Sweden, steering the country’s burgeoning online population to alternatives, like dot-nu.

Today, more than 80% of Mr. Semich’s business is in Sweden, prompting him to open a sales and marketing office in Stockholm. A Swedish parachutist club has registered the Swedish equivalent of “getupandjump.now,” and an advertisement site for Vicks Vaporub uses the equivalent of “wakeup.now.” Some Swedes believe the domain name is Swedish. Mr. Semich charges $30 a year for a domain name, with a minimum two-year commitment. There are about 110,000 domain names using the dot-nu suffix, he says.

Mr. Semich says his private company has annual revenue in the low single-digit millions. He donates 15% to 30% of that to a charitable arm of his operation geared toward developing the Internet on Niue. The money has gone toward an Internet cafe, tower construction, a building designed to protect Internet equipment from cyclones and a $6,000 monthly fee for a telecom link to New Zealand, among other expenses. Between the charity and the business, Mr. Semich employs 12.

Not Getting Rich

Mr. Semich says the venture hasn’t made him wealthy. He lives in the same house he did before he started. His visions of turning his non-Roman alphabet domain-name software into a big business vanished with the Internet bust, which forced him to lay off about a dozen full- and part-time employees at the time. Still, managing dot-nu has proved to be a sustainable business, he says.

By June 2003, the company was able to offer Niueans free wireless Internet, via a series of towers on the island. For many, it not only opened them to the outside world but also enabled an inexpensive way to keep in regular contact with friends and relatives who had left the island years before. The company also got involved in civic affairs on the island, sponsoring the rugby team and Niue’s contestant in a regional beauty pageant.

Nevertheless, four months later, a new telecom minister on the island claimed the operators lacked a proper license. He shut down the service for workers in the government — the largest group of users. The minister, Toke Talagi, requested Icann transfer management of the domain name to the government, charging Mr. Semich and his team with “neo-colonialism” and ignoring the rights of the government.

The government hired an American adviser to help lobby Icann for the change. The adviser charged Mr. Semich with reneging on a promise to give 25% of his profits to the government and, worse, with knowingly registering pornography Web sites. Mr. Semich denies the accusation. The government launched an independent investigation into the allegations.

Mr. Semich says there was never such an agreement. His company had voluntarily agreed to provide free Internet access to the island, which it was doing, he says. He points out that the operators of other domains don’t pay a slice of their proceeds back to governments.

“We agreed to provide free wireless Internet to the government,” he says. “There has never been any other agreement.”

Nevertheless, on strongly Christian Niue, the charges that the country code was being used for pornography sites created a firestorm. Mr. Guest, one of Mr. Semich’s local hires, says the bad publicity hurt business in his motel, the Coral Gardens, forcing him to shut down its restaurant. “They felt we were taking advantage of the nation,” says Mr. Guest, whose wife is from Niue. “We were devastated by some of the things being said of us.”

But soon citizens began to miss the free Internet access. The matter dominated the election for premier in March of last year, where Mr. Talagi, the telecom minister, was considered the favorite. Just days before the vote, the incumbent premier overruled Mr. Talagi by ordering that Mr. Semich’s company could use government-owned towers to extend the Internet to several villages. Mr. Talagi was narrowly defeated.

“The people stood up and said, ‘We want our Wi-Fi,’ ” says Mr. St. Clair, who came to Niue with the Peace Corps in 1994 as a bulldozer mechanic and stayed on to head the construction of the wireless Internet service, called Wi-Fi.

The winner of the election, Mititaiagimene Young Vivian, has taken a more accommodating approach toward Mr. Semich’s company. The independent investigation, which ended late last year, found nothing improper about Mr. Semich’s business or about how he became manager of the domain name in the first place. No evidence exists to support the pornography charge

Still, Premier Young Vivian says he wants to meet with Mr. Semich soon to discuss the domain name. “The key issue is that reasonable benefits should come to Niue,” he says. “That is the goal of any leader.”

Write to Christopher Rhoads at christopher.rhoads@wsj.com

Copyright ©2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved.